A little bit of linkage

I tend to do most of my linking on Twitter these days (and I’m a heartbeat away from setting up a Tumblr page for things that seem too long for Twitter but not really worthy of full-scale blogposts) but I’d be remiss if I didn’t direct people to this amazing series of photographs of London in the early 1880s. All photography is, as Sontag and Barthes remind us, necessarily a record of loss, but in these images of London that sense of loss is (as the author recognises) given added power by the strange absence of people from the streets and buildings depicted, an absence which recasts the city itself as a sort of memento mori.

I tend to do most of my linking on Twitter these days (and I’m a heartbeat away from setting up a Tumblr page for things that seem too long for Twitter but not really worthy of full-scale blogposts) but I’d be remiss if I didn’t direct people to this amazing series of photographs of London in the early 1880s. All photography is, as Sontag and Barthes remind us, necessarily a record of loss, but in these images of London that sense of loss is (as the author recognises) given added power by the strange absence of people from the streets and buildings depicted, an absence which recasts the city itself as a sort of memento mori.

On a rather different note, you might want to check out Sci-Fi-O-Rama, a site dedicated to SF and Fantasy-themed art. There’s usually something good going, but recent features on French SF illustrations, British SF artist Jim Burns (whose work graced the covers of any number of the SF books I read as a teenager in the 1980s) and Australian artist Dan McPharlin are particularly worth checking out.

Elsewhere I can heartily recommend both the excerpt from n+1’s What was the Hipster? in the New York Magazine, a piece which has some very intelligent things to say about the hollowing out of the counter-culture. And if you’ve not seen it before, it’s worth revisiting n+1’s terrific 2005 editorial about the novel and its place in contemporary culture.

And finally, please read the summary of an extraordinary year in climate science that appeared this week on Climate Progress. A lot of what’s there will be familiar to anybody with an interest in the subject, but it’s a piece that should be required reading not just for anybody who doesn’t think climate change is the single biggest issue facing the human race, but for every politician and policy-maker around the world.

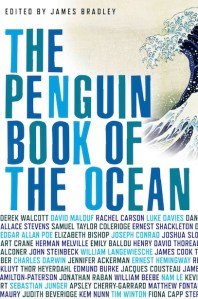

And if you haven’t seen it, perhaps you could cap off the Climate Progress piece with Elizabeth Kolbert’s trenchant analysis of the Republican Party’s war against climate science and climate scientists in this week’s New Yorker. As Kolbert remarked in her chilling 2006 study of climate change, Field Notes from a Catastrophe, “[i]t may seem impossible to imagine that a technologically advanced society could choose, in essence, to destroy itself, but that is what we are now in the process of doing.” (I’d also recommend Kolbert’s excellent piece on the links between declines in zooplankton populations triggered by rising levels of carbon dioxide in the oceans and large-scale change in the ocean’s chemistry, ‘The Darkening Sea’, a piece I came within a hair’s breadth of including in The Penguin Book of the Ocean).