The unlucky life of Captain George Pollard Jnr

This weekend’s New York Times has a fascinating article about the discovery of the wreck of the Whaleship Two Brothers on the French Frigate Shoals, an atoll about 1000km northwest of Honolulu.

The discovery is fascinating for two reasons. The first, and more prosaic, is that there our understanding of life on board Whaleships is largely second-hand. As Ben Simons, of the Nantucket Historical Association points out in the article, “Very little material has been recovered from whale ships that foundered because they generally went down far from shore and in the deepest oceans … we have a lot of logbooks and journals that record disasters at sea, but to be taken to the actual scene of the sunken vessel — that’s really what is so amazing about this.”

But it’s also fascinating because the Two Brothers’ Captain, George Pollard Jnr, was also the captain of the Whaleship Essex, the ship whose sinking by a whale in 1820, and recorded in Owen Chase’s remarkable Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whaleship Essex, was one of the inspirations for Moby Dick.

For those of you who haven’t read Chase’s narrative I urge you to do so: its 60-odd pages are remarkable reading. As Jeremy Harding points out in a piece on Melville in the London Review of Books, contemporary interest in the Essex is, like Melville’s, largely confined to the story of the wreck itself, but as Chase’s narrative reminds us, the wreck is really only the prelude to a far more chilling story, involving the survivors’ journey several thousand kilometres westward, to the Pitcairn Islands, and gradual descent into starvation, cannibalism and madness.

Chase published his account of the wreck and its aftermath in 1821, and some years later it came to the attention of a young Herman Melville (interestingly it was not Melville’s first encounter with the story, which he first heard from Chase’s son, who was also a whaleman, while a crewman on a whaler himself). Later other versions of the disaster would appear, including a detailed account by Charles Wilkes of his conversation with Captain Pollard, and (interestingly) a manuscript held in the Mitchell Library in Sydney which details the experiences of the survivors who chose to remain on Henderson Island in the Pitcairns. These and many more are reproduced in Nathaniel and Thomas Philbrick’s excellent The Loss of the Ship Essex, Sunk by a Whale.

Prior to the wreck, Pollard was described as gentler and more contemplative than the average Nantucket whaleman, and was only 28 when given the command of the Essex. Yet the circumstances of the wreck, and more particularly the descent into cannibalism in the weeks before he and his companions were rescued, changed him.

As the piece in The New York Times points out, in a way the most surprising thing about Pollard’s presence on the Two Brothers is that he actually chose to take on another command. There’s something gut-wrenching about the description of him freezing and having to be physically dragged to a longboat when this second ship foundered, and deeply sad about his subsequent retirement to a position as a night watchman in Nantucket (he actually made one more voyage, upon a merchant vessel).

These days Pollard is mostly remembered as the prototype for Ahab and for his part in the murder and consumption of his cousin Owen Coffin while he and his companions drifted hopelessly in a whaleboat, but in details like the image of him moving through the darkened streets of Nantucket, it’s possible to glimpse a rather different man. Certainly Melville, who visited him after the publication of Moby Dick, was impressed by him, declaring “[t]o the islanders he was a nobody – to me, the most impressive man, tho’ wholly unassuming even humble – that I ever encountered”.

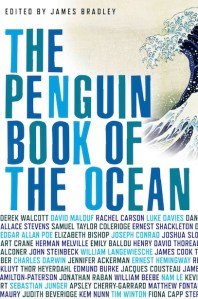

As I say above, the documents relating to the wreck of the Essex are well worth reading, in particular Chase’s Narrative, the opening section of which appears in The Penguin Book of the Ocean. And while I used the Spirit Spout chapter in the collection, if you’re unfamiliar with it I recommend reading the hellish description of the Pequod’s try works, which make the reality of life aboard a Whaleship viscerally real. And finally, if you can track down a copy of Nathaniel Philbrick’s In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex, do: it’s a splendid and harrowing account of a quite remarkable episode in maritime history, and of the fates of Pollard and the other men at its centre.