Narelle Autio, 'The Climb', © Narelle Autio 2001

Some of you may have noticed my piece in The Weekend Australian about summer and the myths of Australianness a couple of weeks back. It was an interesting piece to write, not least because the process of putting it together was, in an odd way, very similar to the processes of remembering and reliving the past that seem to me to so essential to the experience of summer. Certainly while writing it I was reminded very powerfully of my childhood and adolescence in Adelaide, and of the silent, empty streets and wakeful nights.

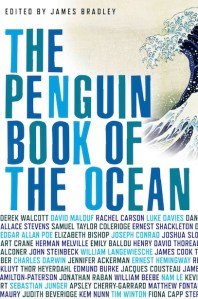

As a writer you have next to no control over the illustrations that appear with your pieces(I think I’ve been asked for a suggestion once and offered them unsolicited twice in all the years I’ve been writing for newspapers). But in the case of this piece I’m not sure I could have chosen something more appropriate, because Review’s Editor, Deborah Jones, chose to use not just an image by Narelle Autio, but her photo ‘The Climb’, which was taken on Brighton Jetty, only a kilometre or so from where I grew up.

I’ve been an admirer of Autio’s photos for a long time, and my partner and I actually own several of them. While the early black and white images of swimmers and surfers bear a passing resemblance to Wayne Levin’s images of bodysurfers, they have an informality and sense of play that’s very much their own, a celebratory aspect that seems to capture something not just of the joy and spontaneity of their subject, but of the odd way that joy and spontaneity seems to exist suspended on the edge of memory.

But the series ‘The Climb’ is a part of has always been my favourite. Partly that’s because the images that comprise it are so vivid and immediate, in particular photos such as ‘Black Marlin’. But it’s also because they capture that oddly informal and shapeless communality that summer holidays often involve, the groups of people and sudden pleasures of caravan parks and camping grounds.

Part of what makes them so beautiful is the sheer saturation of colour, not just the blues of the water but its greenness, the yellow of the sand, even the brooding, impossible purple of late afternoon cloud. I suspect to many it’s a saturation that will seem immediately tropical, but oddly enough I remember standing in front of these pictures in the gallery and being immediately, unshakeably certain that Autio was from South Australia like me. It wasn’t the subjects of the photos – indeed I’m reasonably certain the photo that made me so sure she and I grew up near each other, ‘Orange Car’, is actually of somewhere in New South Wales – rather it was something about the quality of the light and its intensity, the degraded nature of the yellows.

As it turned out I was right: Autio grew up two beaches away from me in Adelaide. But that certainty was a reminder of somethign I’ve long thought about the nature of the Australian experience fo the beach. I keenly remember reading Robert Drewe’s brilliant memoir, The Shark Net, for the first time and being struck by the way it spoke to the summer landscape I knew as a child. Partly that was about it being set amidst the emptiness of sandhills and marram grass of the west coast rather than the cliffs and broken bays one finds on Australia’s east coast, but it was also about the way it made the landscape so palpable, not just the heat and the wind, but the denuded palette of sand and sea and sky, the intense, almost unbearable light.

One of my enduring regrets about The Penguin Book of the Ocean is the fact I couldn’t find a way to include something of Rob’s, not just because he was one of the first two or three writers I thought of when I was planning the book, but because he’s a writer I’ve admired enormously for many years, and whose writing played an important part in inspiring me to become a writer in the first place. I’ve been meaning for some time to write something about the process of putting the anthology together, and the way my desire for it to work as a whole, rather than as a collection of pieces made a lot the decisions for me. But in the end I just couldn’t find a piece by him that spoke to the ocean in the way I needed it to (for a writer whose public image is so indelibly associated with the beach Drewe’s books are usually only interested in landscape in a fairly passing sense, and tend to focus much more on the illusions and betrayals of middle class life).

But I do wonder whether that sense of the differences between the bays and beaches of the east coast and the more denuded landscapes of the south and west coast isn’t one of the reasons Penguin decided to use Autio’s photos to illustrate their recent rerelease of Tim Winton’s coastal memoir, Land’s Edge.

Originally published in 1993, with photographs by Trish Ainslie and Roger Garwood, Land’s Edge is at one level an account of Winton’s enduring love of the ocean, and of the part it played in shaping him. But it’s also a sort of manifesto, a mapping out of the emotional and philosophical territory Winton’s fiction has explored over the years.

To my mind it’s an interesting, if slightly unsatisfying book. I’ve read it twice now, and both times I kept wanting Winton to go further, push harder, dig deeper. But that’s not to say it’s without its pleasures. Certainly it’s fascinating to see the way Winton’s experiences have been woven into the larger fabric of the work, and to be made aware of echoes and allusions between the books and the life which would not otherwise be apparent. It’s also interesting to be reminded how much deeper and darker Winton’s work has grown in the last two decades, and of the manner in which his command of language has kept pace with that deepening: word by word, sentence by sentence I’m not sure there’s any writer working in Australia at the moment (except maybe Delia Falconer) who can match the raw power of Winton’s prose. Even its rough-hewn textures are deceptive, intimations of the steel beneath (in this context you might want to check out my review of Breath from a couple of years back) .

But in a way the real pleasure of this new edition is the book itself, and the use it makes of Autio’s photographs. Penguin have clearly gone to considerable expense to use excellent paper, and it shows, lending both the text and the images a richness and a clarity they might otherwise lack. It’s also convinced Winton to speak publicly, something he doesn’t often do (if you’re interested there’s a long interview with him by Stephen Romei in yesterday’s Australian, complemented by an audio recording of Winton reading from Land’s Edge). If you’d like a taste of the book I’ve reproduced several of the images in it below, and there’s an extract available on Penguin’s website. Likewise if you’d like to see more of Autio’s images you should visit Stills Gallery. Otherwise you can read my piece on summer at The Australian.

Narelle Autio, 'Black Marlin', © Narelle Autio 2001

Narelle Autio, 'Before School', © Narelle Autio 2001

Narelle Autio, 'Orange Car', © Narelle Autio 2001

A couple of posts ago I was talking big about returning to regular posting, something I managed for all of about a week before everything fell in a hole again. I’m not going to make any more rash promises for the moment, simply because I’m still caught in the perfect storm of work and external commitments that has made blogging difficult since the end of last year. But I will try and make sure I do a bit better than I have in recent weeks.

A couple of posts ago I was talking big about returning to regular posting, something I managed for all of about a week before everything fell in a hole again. I’m not going to make any more rash promises for the moment, simply because I’m still caught in the perfect storm of work and external commitments that has made blogging difficult since the end of last year. But I will try and make sure I do a bit better than I have in recent weeks.