I’m sure I’m not alone in feeling 2019 was a year when reading felt necessary, not so much as an escape from the world, but because the kinds of truths it communicates so often seemed an antidote to the increasingly demented and distracted world around us.

I’m sure I’m not alone in feeling 2019 was a year when reading felt necessary, not so much as an escape from the world, but because the kinds of truths it communicates so often seemed an antidote to the increasingly demented and distracted world around us.

Of the books that helped, the best were smart and sane, but also not afraid to engage with the world as it is. This is especially true of the third instalment in Ali Smith’s marvellous Seasons Quartet, Spring, Lucy Ellmann’s massive Ducks, Newburyport, and Max Porter’s glorious Lanny. All three offer marvellous examples of the ways in which fiction can absorb and refract the rhythms and textures of its moment and fashion something revelatory from them. Charlotte Wood’s scabrous and hilarious The Weekend and Elizabeth Strout’s almost casually brilliant Olive Again achieve something similar in their portrait of the lives of the characters at their centre, as well as exploring the often neglected experience of ageing (in the case of The Weekend, it’s particularly fascinating to be reminded of just how bodily a writer Wood is, and of the degree to which all her books are engaged with questions of physicality and decay).

Other books I loved included Tony Birch’s The White Girl, a book whose power lies not just in its subject matter, but in the devastating simplicity and clarity of Birch’s storytelling; Bernadine Evaristo’s Man Booker-winning Girl, Woman, Other; Wendy Erskine’s marvellously compressed and blackly hilarious Sweet Home (seek it out); and Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s portrait of New York life amongst the super-rich, Fleishman is in Trouble, a book that subverts the reader’s expectations in fascinating ways. Likewise I greatly enjoyed Laila Lalami’s The Other Americans, Sean Williams’ Impossible Music, and (although I suspect it’s not the best of the Jackson Brodie books) I loved every moment of Kate Atkinson’s Big Sky.

Other books I loved included Tony Birch’s The White Girl, a book whose power lies not just in its subject matter, but in the devastating simplicity and clarity of Birch’s storytelling; Bernadine Evaristo’s Man Booker-winning Girl, Woman, Other; Wendy Erskine’s marvellously compressed and blackly hilarious Sweet Home (seek it out); and Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s portrait of New York life amongst the super-rich, Fleishman is in Trouble, a book that subverts the reader’s expectations in fascinating ways. Likewise I greatly enjoyed Laila Lalami’s The Other Americans, Sean Williams’ Impossible Music, and (although I suspect it’s not the best of the Jackson Brodie books) I loved every moment of Kate Atkinson’s Big Sky.

I also very much admired both Ben Lerner’s The Topeka School and Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We Are Briefly Gorgeous, a pair of books that have the distinction of being novels by poets that deliberately situate themselves in the unstable, interstitial space between memoir and fiction. In the case of Lerner’s I’m not convinced some of the larger connections he wants to make quite come off, but the precision and brilliance of the writing and his control of structure and the competing perspectives of the characters is so impressive I didn’t care; in the case of the Vuong the parts I found most affecting were in fact in the second half, and in particular his portrait of his relationship with his former lover and their home town.

Sadly I was less excited by the final instalment in Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle, The End. Partly that was to do with the surfaces of the prose – in contrast to the deliberately artless language of the first five volumes a lot of The End has the slightly-too-buffed tone of a New Yorker profile – but it was also because it often felt like the book was rehearsing Knausgaard’s greatest hits (Here I am doing domesticity in excruciating detail! Here I am worrying about my art!). But in the end, even despite moments of brilliance, it just didn’t feel substantial enough to address the concerns that are so wrenchingly explored in the first five.

Sadly I was less excited by the final instalment in Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle, The End. Partly that was to do with the surfaces of the prose – in contrast to the deliberately artless language of the first five volumes a lot of The End has the slightly-too-buffed tone of a New Yorker profile – but it was also because it often felt like the book was rehearsing Knausgaard’s greatest hits (Here I am doing domesticity in excruciating detail! Here I am worrying about my art!). But in the end, even despite moments of brilliance, it just didn’t feel substantial enough to address the concerns that are so wrenchingly explored in the first five.

As I’ve said before, I find the language we use to describe fiction engaged with questions of environmental crisis fairly problematic, but however we choose to classify it, I don’t think there’s any question Lucy Treloar’s Wolfe Island is likely to become one of the classic texts of the field, not least for the incredibly sophisticated way it uses the liminal landscape of the Chesapeake to elide the boundaries between past, present and future to show us we are already living in the midst of a crisis, it’s just that (to borrow William Gibson’s aphorism) it’s unevenly distributed. I also loved Alice Bishop’s incredibly intense and beautifully observed depiction of the Black Saturday bushfires, A Constant Hum, which I would also see as a significant contribution to the literature of environmental crisis in general, and the literature that has grown out of Black Saturday in particular. And I hugely admired Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island, a book that makes fascinating connections between the past and the present by unpicking the intertwined forces of colonialism, capitalism and climate change, and Ben Smith’s starkly observed and very powerfully written breakdown narrative, Doggerland.

Of the speculative fiction I read the two standouts were Tim Maughan’s Infinite Detail and Chuck Wendig’s Wanderers. If you haven’t read the Maughan, make the time: it’s a startlingly intelligent and profoundly political interrogation of surveillance culture and late capitalism. The Wendig is also wonderful: a seamless fusion of horror and science fiction that manages to be oddly timeless and incredibly topical. Ted Chiang’s Exhalation and Helen Phillips’ The Need are also terrific, as are Garth Nix’s wildly enjoyable Angel Mage and Margaret Morgan’s sleekly subversive The Second Cure, a book that feels more prescient almost by the hour. And although it seems to have passed a lot of people by, Ann Leckie’s The Raven Tower is an absolutely fascinating exercise in what is as much a form of environmental writing as fantasy.

Of the speculative fiction I read the two standouts were Tim Maughan’s Infinite Detail and Chuck Wendig’s Wanderers. If you haven’t read the Maughan, make the time: it’s a startlingly intelligent and profoundly political interrogation of surveillance culture and late capitalism. The Wendig is also wonderful: a seamless fusion of horror and science fiction that manages to be oddly timeless and incredibly topical. Ted Chiang’s Exhalation and Helen Phillips’ The Need are also terrific, as are Garth Nix’s wildly enjoyable Angel Mage and Margaret Morgan’s sleekly subversive The Second Cure, a book that feels more prescient almost by the hour. And although it seems to have passed a lot of people by, Ann Leckie’s The Raven Tower is an absolutely fascinating exercise in what is as much a form of environmental writing as fantasy.

In recent years writing about the natural world has taken on a new urgency, charged not just with helping us see the world in new ways but with bearing witness to the scale of the transformation taking place around us. Of the non-fiction concerned with these questions I read this year, three books stood head and shoulders above the rest. The first was Robert Macfarlane’s stunning Underland. I’ve been a huge admirer of Macfarlane’s work since The Wild Places, but Underland is invested with an urgency and a depth of thinking that pushes it to a new level. It’s an astonishing book.

I was also hugely impressed by Sophie Cunningham’s wonderfully peripatetic City of Trees. Like Underland it’s a book that’s simultaneously focussed on the particular and the global, and asks vital and profound questions about our responsibilities to the past and the future. I loved it.

And finally there was Barry Lopez’s Horizon. If I had to make a list of books that I can honestly say changed my life, Lopez’s Arctic Dreams would be close to the top. I’m not sure Horizon is as easy to admire as Arctic Dreams – it’s a much more conflicted, troubled work, that’s closer in many ways to the kinds of autobiographical writing Lopez published in About This Life, but that sense Lopez is grappling with his legacy and trying to make sense of his larger project is part of what makes it so fascinating, and so profound. It’s a remarkable book, and one I suspect I’ll be returning to.

I also very much admired a number of the essays in Kathleen Jamie’s splendid Surfacing, David Wallace-Wells’ brilliant and completely uncompromising synthesis of the bad news on climate change, The Uninhabitable Earth, and Ian Urbina’s thrilling and often deeply confronting portrait of life on the high seas, The Outlaw Ocean. And closer to home I was incredibly impressed by Vicki Hastrich’s illuminating and expansive essays about the waterways of the central coast, memory and seeing, Night Fishing. And although it’s not about the natural world, Shoshana Zuboff’s The Age of Surveillance Capitalism should be compulsory reading for everybody.

I also very much enjoyed a few things from previous years, in particular Sigrid Nunez’s The Friend, Robbie Arnott’s magic realist Tasmanian Gothic, Flames, Rebecca Makkai’s wonderfully observed The Great Believers and Natalia Ginzburg’s Family Lexicon. I also finally got around to Patricia Lockwood’s Priestdaddy, which is precisely as good as everybody says it is.

As always there are also a number of things I didn’t get to but hopefully will in the next few weeks, in particular Yoko Ogawa’s The Memory Police, Ann Patchett’s The Dutch House, Christos Tsiolkas’ Damascus, Alice Robinson’s The Glad Shout and Namwali Serpell’s The Old Drift. In the meantime I hope you all have a wonderful holiday season and that 2020 is an improvement on 2019.

I’m sure I’m not alone in feeling 2019 was a year when reading felt necessary, not so much as an escape from the world, but because the kinds of truths it communicates so often seemed an antidote to the increasingly demented and distracted world around us.

I’m sure I’m not alone in feeling 2019 was a year when reading felt necessary, not so much as an escape from the world, but because the kinds of truths it communicates so often seemed an antidote to the increasingly demented and distracted world around us. Other books I loved included Tony Birch’s The White Girl, a book whose power lies not just in its subject matter, but in the devastating simplicity and clarity of Birch’s storytelling; Bernadine Evaristo’s Man Booker-winning Girl, Woman, Other; Wendy Erskine’s marvellously compressed and blackly hilarious Sweet Home (seek it out); and Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s portrait of New York life amongst the super-rich, Fleishman is in Trouble, a book that subverts the reader’s expectations in fascinating ways. Likewise I greatly enjoyed Laila Lalami’s The Other Americans, Sean Williams’ Impossible Music, and (although I suspect it’s not the best of the Jackson Brodie books) I loved every moment of Kate Atkinson’s Big Sky.

Other books I loved included Tony Birch’s The White Girl, a book whose power lies not just in its subject matter, but in the devastating simplicity and clarity of Birch’s storytelling; Bernadine Evaristo’s Man Booker-winning Girl, Woman, Other; Wendy Erskine’s marvellously compressed and blackly hilarious Sweet Home (seek it out); and Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s portrait of New York life amongst the super-rich, Fleishman is in Trouble, a book that subverts the reader’s expectations in fascinating ways. Likewise I greatly enjoyed Laila Lalami’s The Other Americans, Sean Williams’ Impossible Music, and (although I suspect it’s not the best of the Jackson Brodie books) I loved every moment of Kate Atkinson’s Big Sky. Sadly I was less excited by the final instalment in Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle, The End. Partly that was to do with the surfaces of the prose – in contrast to the deliberately artless language of the first five volumes a lot of The End has the slightly-too-buffed tone of a New Yorker profile – but it was also because it often felt like the book was rehearsing Knausgaard’s greatest hits (Here I am doing domesticity in excruciating detail! Here I am worrying about my art!). But in the end, even despite moments of brilliance, it just didn’t feel substantial enough to address the concerns that are so wrenchingly explored in the first five.

Sadly I was less excited by the final instalment in Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle, The End. Partly that was to do with the surfaces of the prose – in contrast to the deliberately artless language of the first five volumes a lot of The End has the slightly-too-buffed tone of a New Yorker profile – but it was also because it often felt like the book was rehearsing Knausgaard’s greatest hits (Here I am doing domesticity in excruciating detail! Here I am worrying about my art!). But in the end, even despite moments of brilliance, it just didn’t feel substantial enough to address the concerns that are so wrenchingly explored in the first five. Of the speculative fiction I read the two standouts were Tim Maughan’s Infinite Detail and Chuck Wendig’s Wanderers. If you haven’t read the Maughan, make the time: it’s a startlingly intelligent and profoundly political interrogation of surveillance culture and late capitalism. The Wendig is also wonderful: a seamless fusion of horror and science fiction that manages to be oddly timeless and incredibly topical. Ted Chiang’s Exhalation and Helen Phillips’ The Need are also terrific, as are Garth Nix’s wildly enjoyable Angel Mage and Margaret Morgan’s sleekly subversive The Second Cure, a book that feels more prescient almost by the hour. And although it seems to have passed a lot of people by, Ann Leckie’s The Raven Tower is an absolutely fascinating exercise in what is as much a form of environmental writing as fantasy.

Of the speculative fiction I read the two standouts were Tim Maughan’s Infinite Detail and Chuck Wendig’s Wanderers. If you haven’t read the Maughan, make the time: it’s a startlingly intelligent and profoundly political interrogation of surveillance culture and late capitalism. The Wendig is also wonderful: a seamless fusion of horror and science fiction that manages to be oddly timeless and incredibly topical. Ted Chiang’s Exhalation and Helen Phillips’ The Need are also terrific, as are Garth Nix’s wildly enjoyable Angel Mage and Margaret Morgan’s sleekly subversive The Second Cure, a book that feels more prescient almost by the hour. And although it seems to have passed a lot of people by, Ann Leckie’s The Raven Tower is an absolutely fascinating exercise in what is as much a form of environmental writing as fantasy.

As promised the other day, I thought I’d do a quick roundup of some of the books I enjoyed most this year. Right at the top of my list are two books I loved quite immoderately, Richard Powers’

As promised the other day, I thought I’d do a quick roundup of some of the books I enjoyed most this year. Right at the top of my list are two books I loved quite immoderately, Richard Powers’  A number of the Australian books I read this year were from last year as well; I particularly admired Michelle de Kretser’s The Life to Come, Ryan O’Neill’s

A number of the Australian books I read this year were from last year as well; I particularly admired Michelle de Kretser’s The Life to Come, Ryan O’Neill’s  And finally, my non-fiction reading was a bit spotty, but a lot of what I did read was terrific, and of that, the absolute highlights were Caspar Henderson’s prismatic A New Map of Wonders, Joy McCann’s wonderfully rich and expansive history of the Southern Ocean,

And finally, my non-fiction reading was a bit spotty, but a lot of what I did read was terrific, and of that, the absolute highlights were Caspar Henderson’s prismatic A New Map of Wonders, Joy McCann’s wonderfully rich and expansive history of the Southern Ocean,

About fifteen years ago, when I was working The Resurrectionist, Ivor Indyk from Giramondo Publishing approached me and asked me whether I’d be interested in writing a piece about my work in progress for Heat. Although the book was slowly moving toward completion it had been an incredibly difficult process, both emotionally and creatively, and at first I wasn’t sure whether I really wanted to open up about how hard it had been. Eventually I decided I would, but in the process I found myself having to think about a whole series of questions about the way I worked, what I thought fiction did, and the ways in which my experiences with depression had shaped both the book and my life and work more generally.

About fifteen years ago, when I was working The Resurrectionist, Ivor Indyk from Giramondo Publishing approached me and asked me whether I’d be interested in writing a piece about my work in progress for Heat. Although the book was slowly moving toward completion it had been an incredibly difficult process, both emotionally and creatively, and at first I wasn’t sure whether I really wanted to open up about how hard it had been. Eventually I decided I would, but in the process I found myself having to think about a whole series of questions about the way I worked, what I thought fiction did, and the ways in which my experiences with depression had shaped both the book and my life and work more generally.

It’s nearly the holidays, so I thought I’d brush the cobwebs off the website and pull together a list of some of the books I’ve loved this year.

It’s nearly the holidays, so I thought I’d brush the cobwebs off the website and pull together a list of some of the books I’ve loved this year. I also loved Alan Hollinghurst’s glorious The Sparsholt Affair, a book that is so gorgeously and wittily constructed sentence by sentence and so wonderfully well-observed I spent the whole final third being sorry it was going to end. I was also hugely impressed by Megan Hunter’s slim but beautiful story of a flooded England, The End We Start From, Philip Pullman’s triumphant return to the world of Northern Lights, La Belle Sauvage (a book that also, not coincidentally, I suspect, features an epochal flood), Jennifer Egan’s sleekly oblique

I also loved Alan Hollinghurst’s glorious The Sparsholt Affair, a book that is so gorgeously and wittily constructed sentence by sentence and so wonderfully well-observed I spent the whole final third being sorry it was going to end. I was also hugely impressed by Megan Hunter’s slim but beautiful story of a flooded England, The End We Start From, Philip Pullman’s triumphant return to the world of Northern Lights, La Belle Sauvage (a book that also, not coincidentally, I suspect, features an epochal flood), Jennifer Egan’s sleekly oblique  I’m not sure it makes much dividing science fiction and fantasy publishing from literary publishing any more, especially not when the concerns so many of the best novels on both sides of the divide are exploring are so similar (and indeed, when so many writers move so fluidly back and forth), a point that’s underlined by the fact stories in Carmen Maria Machado’s hugely impressive Her Body and Other Parties were published in

I’m not sure it makes much dividing science fiction and fantasy publishing from literary publishing any more, especially not when the concerns so many of the best novels on both sides of the divide are exploring are so similar (and indeed, when so many writers move so fluidly back and forth), a point that’s underlined by the fact stories in Carmen Maria Machado’s hugely impressive Her Body and Other Parties were published in  My favourite Australian novel was Jane Rawson’s fabulously weird remaking of the historical novel, From the Wreck, but I also loved Krissy Kneen’s science fictional exploration of post-humanity and desire and intimacy, An Uncertain Grace, Ashley Hay’s delicate exploration of post-natal depression and the complex entanglements of place and love, A Hundred Small Lessons and Kathryn Heyman’s brutal but necessary Storm and Grace. I also enjoyed Shaun Prescott’s unsettling excursion into the haunted spaces of central west NSW, The Town, Sally Abbott’s powerful and deeply unsettling exploration of climate change and similar questions about Australia’s inland communities, Closing Down, and Jock Serong’s incredibly powerful excursion into the charged territory of Australia’s refugee policy, On The Java Ridge (a book that has one of the most viscerally intense central sections I’ve read in a long, long time). And while it wasn’t strictly a 2017 book, I also really enjoyed Mark Smith’s post-apocalyptic young adult novel, The Road to Winter, and I’m very much looking forward to the sequel, Wilder Country (which did come out in 2017).

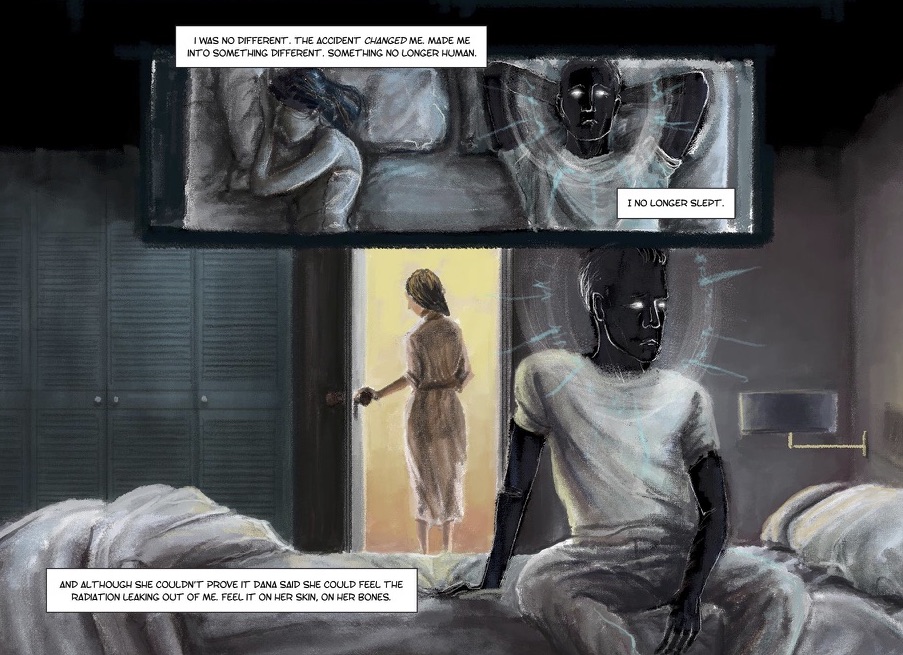

My favourite Australian novel was Jane Rawson’s fabulously weird remaking of the historical novel, From the Wreck, but I also loved Krissy Kneen’s science fictional exploration of post-humanity and desire and intimacy, An Uncertain Grace, Ashley Hay’s delicate exploration of post-natal depression and the complex entanglements of place and love, A Hundred Small Lessons and Kathryn Heyman’s brutal but necessary Storm and Grace. I also enjoyed Shaun Prescott’s unsettling excursion into the haunted spaces of central west NSW, The Town, Sally Abbott’s powerful and deeply unsettling exploration of climate change and similar questions about Australia’s inland communities, Closing Down, and Jock Serong’s incredibly powerful excursion into the charged territory of Australia’s refugee policy, On The Java Ridge (a book that has one of the most viscerally intense central sections I’ve read in a long, long time). And while it wasn’t strictly a 2017 book, I also really enjoyed Mark Smith’s post-apocalyptic young adult novel, The Road to Winter, and I’m very much looking forward to the sequel, Wilder Country (which did come out in 2017). On the comics front I was hugely impressed by Emil Ferris’ extraordinarily dense and marvellously idiosyncratic My Favourite Thing is Monsters, and while there were fewer moments of excitement on the mainstream comic front, I’m completely in love with Jeff Lemire’s Black Hammer (and its new offshoot, Sherlock Frankenstein) and I continue to be surprised by how much I’m engaged by Ed Brubaker’s reworking of the trope of the lone vigilante, Kill Or Be Killed. But the comic I loved most this year was one I should have read a decade ago but never quite got around to, Alison Bechdel’s astonishing Fun House (and which I’m going to mention here simply because it’s so good I think everybody should read it).

On the comics front I was hugely impressed by Emil Ferris’ extraordinarily dense and marvellously idiosyncratic My Favourite Thing is Monsters, and while there were fewer moments of excitement on the mainstream comic front, I’m completely in love with Jeff Lemire’s Black Hammer (and its new offshoot, Sherlock Frankenstein) and I continue to be surprised by how much I’m engaged by Ed Brubaker’s reworking of the trope of the lone vigilante, Kill Or Be Killed. But the comic I loved most this year was one I should have read a decade ago but never quite got around to, Alison Bechdel’s astonishing Fun House (and which I’m going to mention here simply because it’s so good I think everybody should read it).